Gruen was involved in numerous Lawsuits were numerous, perhaps as many as 50.

I will spotlight a few on this page, starting with...

1951 GRUEN WATCH CO v. ARTISTS ALLIANCE

This first case caught my attention as being just too weird to pass up on posting! Who knew?!

In a 1951 case between Gruen and Artists Alliance, Gruen alleges that they were swindled out of Product Placement in a films "Love Happy" staring the Marx Brothers.

I'll summarize using words in the actual complaint.... it's too weird to believe...

Gruen constructed a specially designed advertising display consisting of a very large neon illuminated clock with the words "Gruen Watch Time" at the top. The clock had a huge swinging pendulum and Harpo Marx swung from this in a Hollywood "chase" sequence. This display was made and used in the filming in 1948.

Then, in Sept 1948, the film's publicity director wrote Gruen, sending them photos from the filming using Gruen's clock, suggested Gruen might want to send watches to be displayed in connection with advertising the picture.

Then, after Gruen had told people they would appear in the film, they were again contacted, this time with a demand that Gruen pay $25,000 (over $250,000 today!!!) to help cover the costs of advertising the film and Gruen watches. The bill came with a threat to not just remove the Gruen name from the watch prop in the film, but to replace Gruen with BULOVA!

Recall that this giant prop was actually built by Gruen, presumably at some hefty expense.

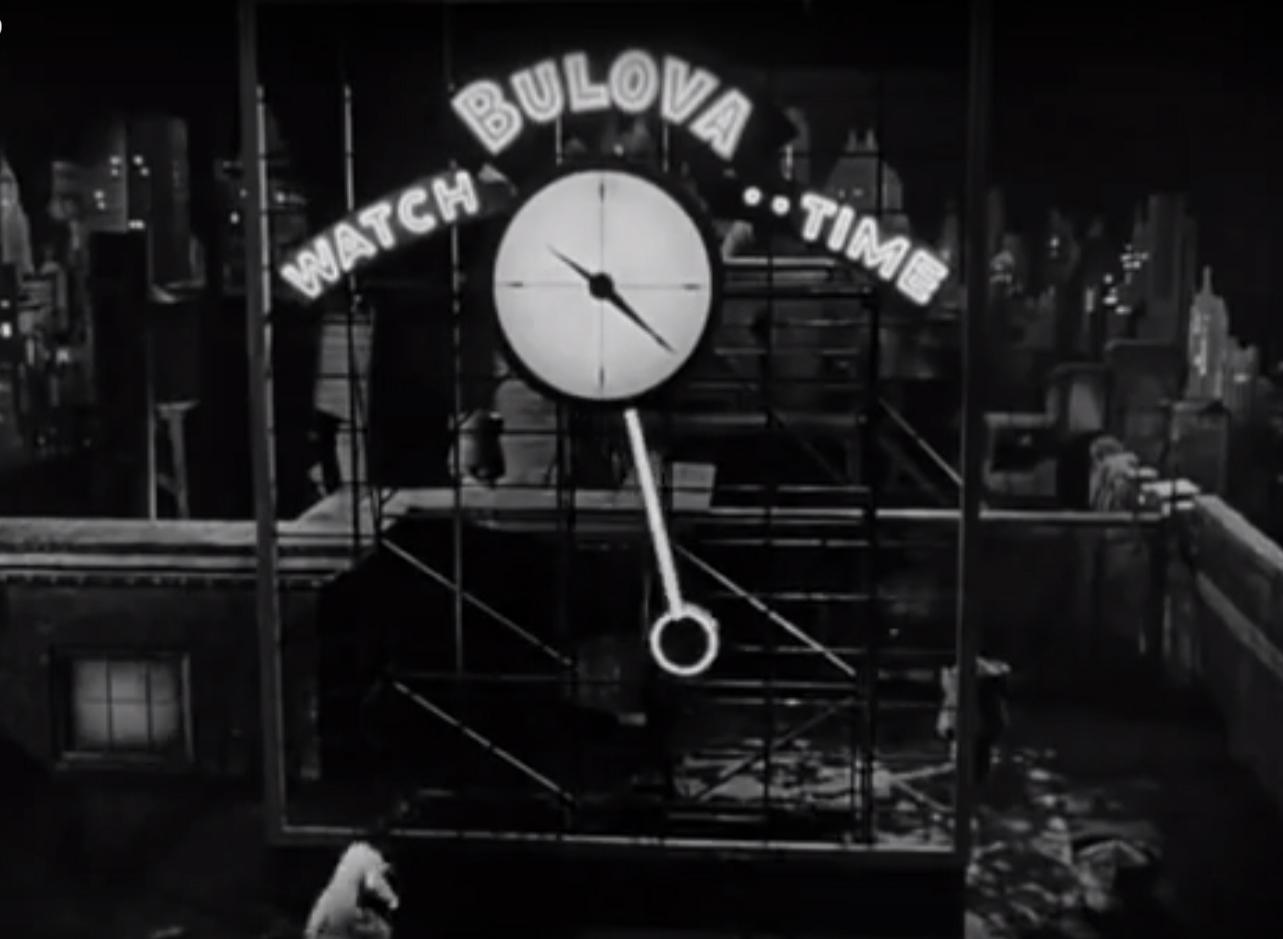

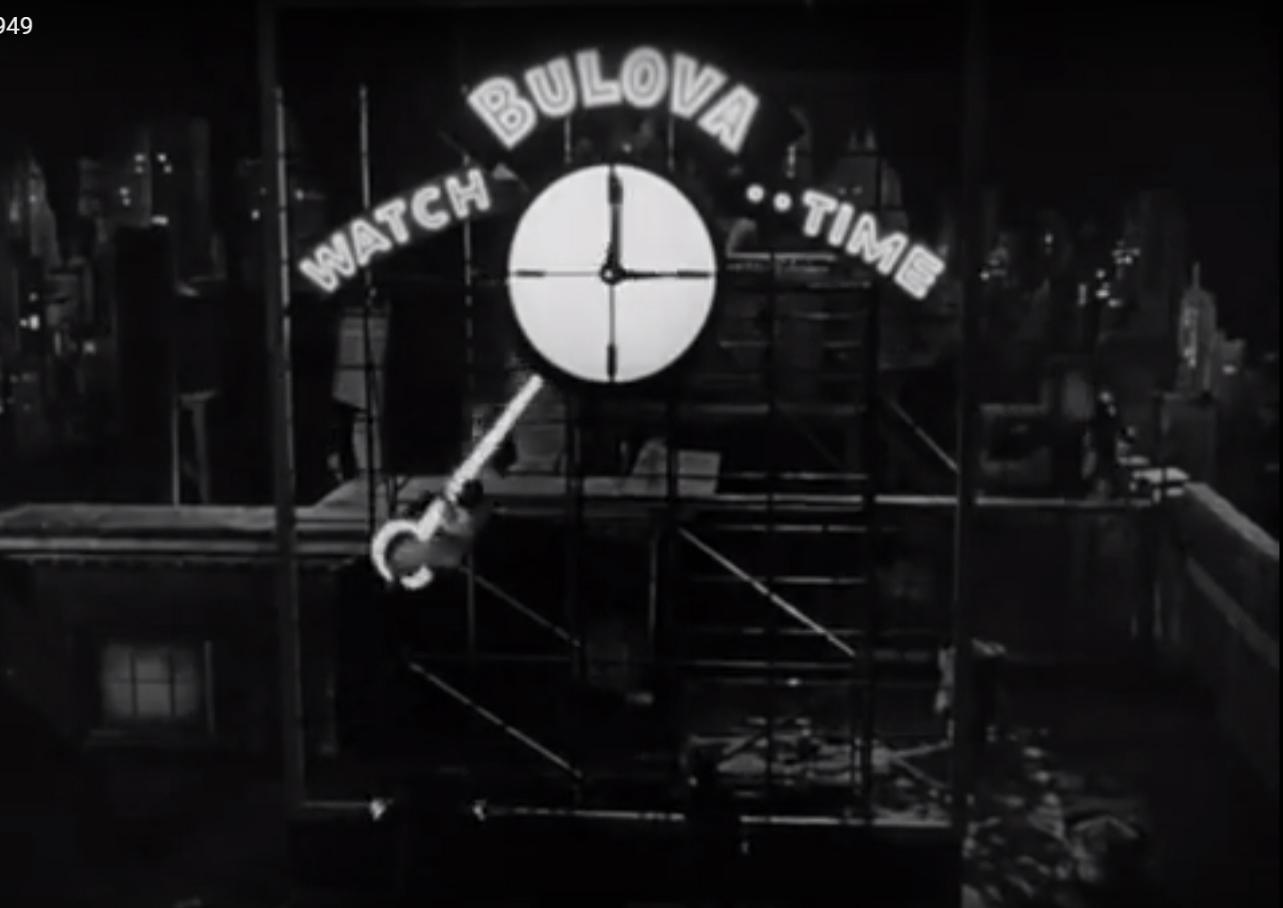

When I looked up the film Love Happy on YouTube to see what the outcome of this threat was.... I was shocked to see at 1:19:28....

Looks like Gruen didn't pay up the extortion and that the film's producers went through with their threats to bump Gruen from their own sign. Harsh!

Below is the full text from the legal brief.

GRUEN WATCH CO. v. ARTISTS ALLIANCE

No. 12528.

191 F.2d 700 (1951)

GRUEN WATCH CO. v. ARTISTS ALLIANCE, Inc. et al.

United States Court of Appeals Ninth Circuit.

September 12, 1951.

Attorney(s) appearing for the Case

Taft, Stettinius & Hollister, Cincinnati, Ohio, Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, Henry F. Prince, Frederic H.

Sturdy and Richard E. Davis, Los Angles, Cal., for appellant.

Mitchell, Silberberg & Knupp and Leonard A. Kaufman, Los Angeles, Cal., for appellees.

Before BIGGS, HEALY and BONE, Circuit Judges.

BIGGS, Circuit Judge.

The appeal at bar is from a final judgment entered on March 8, 1950, dismissing the plaintiff's (Gruen's)

second amended and supplemental complaint on the ground that it failed to state a claim on which relief

could be granted and from an order made concurrently striking portions of the complaint on motion of the

producer defendants who will be referred to usually hereinafter as Cowan. Jurisdiction in the instant case

is based on diversity and judisdictional amount, Gruen being an Ohio corporation and the defendants

variously being either citizens of California or of New York.

1

Bulova Watch Company, Inc. (Bulova) has

been also named as a party.

The second amended and supplemental complaint alleges the following: In May of 1948, Kline, a "public

relations" man and an agent for Gruen, at Cowan's instance and request obtained an agreement from four

advertisers represented by him for the use of displays and signs in a forthcoming motion picture, "Love

Happy", to be produced by Cowan. Gruen was one of the four advertisers. Kline's letter of June 22, 1948,

attached to the complaint as "Exhibit A", the terms of which were accepted by the producers, formed the

basis of the contract.

[191 F.2d 702]

Most of the letter is pertinent and we quote it in its entirety:

"Walter E. Kline "Public Relations "Lester Cowan Productions "Gentlemen:

"In confirmation of our present understanding it is hereby agreed as follows:

"1. You have advised me of your plans and intentions to produce a feature length sound and talking motion

picture presently entitled `Hearts and Diamonds [subsequently named "Love Happy"]' in which the Marx

Brothers will be co-starred. You have further advised me that certain scenes and sequences in the picture

will be devoted to the activities of one or more of the Marx Brothers in connection with various advertisings

and displays.

"2. Pursuant to your request therefor I have obtained from the hereinafter specified advertisers agreements

in connection with your use of their respective signs and displays. Such advertisers and their signs and

displays are as follows:

"a. The General Petroleum Corporation whose advertising sign displays the `Flying Red Horse' in

connection with its sale of Mobilgas.

"b. The Fisk Tire Company whose advertising sign displays a boy and a candle bearing the slogan `Time

to Retire.'

"c. The Brown and Williamson Tobacco Corporation (Kool Cigarettes), Ted Bates Agency.

"d. The Gruen Watch Company.

"e. One or more other companies using advertising signs or displays which may hereafter be included in

the terms of this agreement by our mutual written statement to that effect.

"3. You understand that some expense will be incurred by me or my principals in preparing for your use

the above specified advertisements or displays. On behalf of my respective principals I am privileged to

state that the cost of constructing such signs and displays which [sic] will be borne by my respective

principals provided that their respective advertising signs and displays are included in the final version of

your picture as released to the general public; and further provided that such picture is actually released to

the general public not later than January 1, 1950.

"4. It is therefor [sic] understood and agreed that you will bear the cost incurred in connection with the

construction and erection of any or all of such signs or displays which are not actually included in the

picture substantially in the manner presently represented to you; it being further understood that you will

bear the cost of all of such signs and displays if the said picture is not released to the general public prior

to January 1, 1950. At your request, of course, we shall furnish you with an itemized statement of all costs

so incurred.

"If the above is in accordance with your understanding of our agreement, please indicate the same by

signing in the space provided therefor below.

"Very truly yours, "(s) Walter E. Kline. "Approved and Accepted: "Lester Cowan Productions (An Artist

Alliance, Incorporated Production by Lester Cowan.) "By (s) Lester Cowan."

The second amended and supplemental complaint alleges that pursuant to the letter Gruen constructed a

specially designed advertising display consisting of a very large neon-illuminated clock with the words,

"Gruen Watch Time," at the top. The clock had a huge swinging pendulum and Harpo Marx swung from

this in a Hollywood "chase" sequence; that Gruen's display was used by Cowan in filming the picture in

August 1948; that in September and October 1948, Armstrong, Cowan's publicity director wrote Gruen

sending it photographs of the action of the Gruen watch sign in the film and suggested that Gruen might

desire to send watches to be displayed in connection with advertising the picture. The complaint alleges

also that shortly thereafter and before the film was completed, Gruen gave permission to Cowan for the

publication of an article entitled "Hairbreadth Harpo" with accompanying photographs in the February 7,

1949, issue of Life Magazine; that at about the same time Gruen released publicity material

[191 F.2d 703]

based on the film to jewelers' trade papers; that thereafter, on a date not set forth in the complaint,

Cowan demanded that Gruen pay $25,000 to Cowan for the purpose of jointly advertising the motion

picture and Gruen's watches; and that Gruen was advised by Cowan that unless the money was paid

Cowan would remove the shots of Gruen's display from the film and substitute a sequence advertising

the product of one of Gruen's competitors. The complaint goes on to allege that Gruen refused to

comply and that Cowan, without authority from Gruen, altered the plaintiff's display by removing the

name "Gruen" therefrom and substituting the name "Bulova" in its place, and that the motion picture

was released to the public with the name "Bulova" substituted on the display in place of "Gruen". It is

also alleged that Bulova consciously and maliciously interfered with and damaged Gruen's contract

rights.

The complaint prays that Cowan be ordered to delete the name "Bulova" from the motion picture and to

restore the name "Gruen" and that Cowan be enjoined permanently from including in the motion picture

any shot of any display advertising in any way the product of Bulova, or of any other competitor of Gruen;

that Bulova and its agents be enjoined permanently from advertising their products jointly with the motion

picture and from using Gruen's display in the picture. Gruen also seeks both general and exemplary or

punitive damages. Cowan and Bulova moved to dismiss the complaint and the court below, not being able

to see any foundation for liability against either Cowan or Bulova, granted the motion. D.C., 89 F.Supp.

564. The appeal at bar followed.

The trial court construed paragraphs 3 and 4 of the letter agreement of June 22, 1948 as providing that

Kline's principal, Gruen, would bear the cost of construction of the display, if it was included in the "final

version" of the picture, but if the display was not included in the final version of the picture then Cowan

should bear the cost of the construction of the display. According to the view of the court below, since

Gruen's display was not included in the final version, Cowan's liability was limited to the reimbursement

of Gruen for money expended by the latter in preparing the display. In short, the court below adhered very

strictly to the terms of the letter of June 22, treating it as constituting the whole agreement between the

parties and not subject to any variation or enlargement by parole evidence.

It appears from the allegations of the complaint that the contract was made in California and was to be

executed there at least in large part. The law of California therefore governs. It is the law of California,

absent any ambiguity, that the provisions of a contract as written will govern. See Barham v. Barham, 33

Cal.2d 416, 423, 202 P.2d 289, 293, and Pacific Portland Cement Co. v. Food Mach. & Chem. Corp., 9

Cir., 178 F.2d 541, 548-553. The letter contract contains four separate paragraphs. The first paragraph states

that Cowan had advised Kline of Cowan's "plans and intentions" in respect to a motion picture. The second

paragraph refers to the "request" made by Cowan to Kline that he obtain "agreements" from his, Kline's,

customers for the use of their displays in the picture. Explicit in the paragraph is the suggestion that Kline

had procured contracts from his clients, including Gruen, and that they would furnish displays in accordance

with the provisions of these contracts. Kline, apparently, was acting as agent both for Gruen and for Cowan.

Conceivably, the terms of the agreement made by Kline for Gruen in connection with the motion picture

could be immaterial but this is not demonstrated by the pleading. Indeed, the contrary must be assumed at

this stage of the proceeding.

Paragraph three of the letter contract provides that the cost of the displays will be borne by Kline's clients,

including Gruen, if the displays are "included" in the "final version" of the picture as released to the general

public. The word "included" is also used in the fourth paragraph but it is modified by the adverb "actually"

and the phrase "actually included" is modified by the clause "substantially in the manner presently

represented to you". What is the difference in meaning between the

[191 F.2d 704]

word "included" used in paragraph three and the phrase "actually included" used in paragraph four?

What was the manner of inclusion "presently represented" to Cowan? Does not the limiting phrase refer

to the "agreements" designated in paragraph two? Some significance must be attributed to the use by

Kline of the word "actually", at least at this stage of the proceeding. Substantial ambiguities appear on

the face of the letter of June 22, 1948. Another very substantial ambiguity, albeit a less apparent one,

arises from the use of the phrase "advertising signs and displays" and the phrase "signs and displays"

variously employed in paragraphs two, three and four. If, as the complaint alleges, Cowan made use of

Gruen's display by simply striking out therefrom the word "Gruen" and substituting in lieu thereof the

word "Bulova", did or did not Cowan use Gruen's display in the final version of the picture? Under the

circumstances, was there not an implied undertaking that if Cowan made use of Gruen's sign it would do

so only in order to advertise Gruen's product?

There are many latent ambiguities as well. Did or did not the letter memorandum imply an obligation on

the part of Cowan to use Gruen's name on Gruen's display, if the display was used at all? Was Cowan

entitled under the provisions of the letter agreement or the contract made by Kline with Gruen to exact

$25,000 from Gruen to be employed, according to Gruen, as a joint fund for advertising the picture and

Gruen watches? If Cowan was not entitled to make this exaction, was Cowan guilty of breach of contract?

These questions also are ones which cannot be answered by an examination of the letter contract.

We are of the opinion that contemporaneous agreements not inconsistent with the terms of the letter may

be introduced here, where reference is made to other agreements. Schmidt v. Cain, 95 Cal.App. 378, 380,

272 P. 803, 804. See also Henika v. Lange, 55 Cal.App. 336, 338, 203 P. 798, 800, in which it is stated, "*

* * where a portion only of the contract between the parties has been reduced to writing it is proper to allow

parol evidence as to the portion of the agreement not included in writing. Johnson v. [D. H.] Bibb Lumber

Co., 140 Cal. 95, 98, 73 P. 730 [731]; Williams v. Ashhurst [Oil, L. & D. Co.] 144 Cal. 619, 78 P. 28." See

also California Annotation, Restatement, Contracts. Extrinsic evidence also may be employed to resolve

the ambiguities and uncertainties of the contract. Boddy-Steffner Co. v. Flotill Products, 63 Cal.App.2d

555, 561-562, 147 P.2d 84, 88; Detsch & Co. v. American Products Co., 9 Cir., 152 F.2d 473-474, and

Simmons v. California Institute of Technology, 34 Cal.2d 264, 209 P.2d 581.

Gruen contends that by reason of Cowan's conduct during the nine months' period subsequent to the

execution of the letter agreement Cowan became obligated to use Gruen's name on Gruen's display and that

in any event Cowan is estopped by Cowan's conduct and Gruen's reliance thereon to deny that Cowan had

elected to use Gruen's sign and display. Expressly, we do not pass upon these allegations in order to

determine whether or not they present causes of action available to Gruen pursuant to California law. Under

our disposition of the instant appeal an opportunity will be afforded to the parties to present any evidence

pertinent to the issues set up by the pleading, and any attempt to lay down applicable principles of law in

the absence of findings of fact by the trial court would be to do little more in all probability than to render

an advisory opinion.

As to the defendant Bulova the complaint specifically alleges that Bulova knowingly and maliciously

interfered with Gruen's contract rights. Paragraph XVI alleges that Bulova, conspiring with Cowan, altered

the motion picture containing Gruen's display by removing the word "Gruen" and substituting in lieu thereof

the word "Bulova"; that these acts were committed in order to deprive Gruen of the "reasonably [to be]

expected fruits of its agreements and understandings" with Cowan and to injure Gruen's business,

competitive position, dealer relations, reputation and good will. It is the law of

[191 F.2d 705]

California that intentional and unjustifiable interference with contractual relations is actionable. Speegle

v. Board of Fire Underwriters, 29 Cal.2d 34, 172 P.2d 867. This is true whether the contract is "at the

will" of the parties or not. See Romano v. Wilbur Ellis & Co., 82 Cal.App.2d 670, 186 P.2d 1012. It does

not necessarily follow, therefore, assuming that Cowan had the right not to proceed with Gruen's

display under the contract that Bulova could be substituted for Gruen without liability on the part of

either Bulova or Cowan. This issue is one which again cannot properly be determined on the pleadings.

On occasion motions to dismiss supply a useful technique for the prompt disposition of suits, and the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure which permit judgment on the pleadings are useful indeed. But it must be

borne in mind that in many a suit such a motion cannot take the place of submission of evidence and of

findings of fact and conclusions of law. Every motion to dismiss must be viewed in the light of Rule 8(a),

(e) and (f), Fed. Rules Civ.Proc. 28 U.S.C.A. Such a motion should not be granted unless it appears clearly

that no cause of action is stated. The court below was not concerned with the question as to whether Gruen

had a claim on which it is ultimately entitled to prevail but whether the second amended and supplemental

complaint, construed in the light most favorable to Gruen, and with all doubts resolved in favor of the

complaint's sufficiency, stated a claim on which relief could be granted. See Leimer v. State Mut. Life

Assur. Co., 8 Cir., 108 F.2d 302, 304. Gruen has set forth at least two grounds, viz., breach of contract and

tort, on which, if the proof sustains the allegations, it can recover from Cowan, and has also set forth a

ground viz., tortious interference with a contract, if proof can be supplied, on which it can recover from

Bulova.

The order of dismissal, appealed from, granting the motions of all of the defendants to dismiss the action,

was filed March 6, 1950, and judgment was entered thereon on March 8, 1950. Prior thereto, on February

27, 1950, according to the record, albeit docket entries of this date are none too clear, a "Minute Order to

Dismiss" was entered. The second item of this order granted the defendants' motion to strike parts of the

second amended and supplemental complaint, as designated under heading "III" of the "Statement of

Points" filed by Gruen on appeal. To the end that the court below may have a clear field for the

reconsideration of the entire subject matter of the instant suit, we vacate this part of the Minute Order. The

judgment entered on March 8, 1950 on the order of dismissal filed March 6, 1950 is reversed. The cause is

remanded with the direction to proceed in accordance with this opinion.

FootNotes

1. Artists Alliance, Inc., Lester Cowan Productions and Lester Cowan, individually, are citizens of

California. The Bulova Watch Co. is a New York corporation.